Posted By Khuram Farooq and Michael Schaeffer [i]

The traditional program budgeting structure is program, sub-program and activity. Can we simplify this structure? Is the ‘activity’ element of this classification really necessary? Why ‘activity’? The conventional argument is that ‘activity’ will be used to capture ‘projects’ or capital expenditures under sub-programs. This may be a valid explanation on paper. In practice, however, the concept of ‘activity’ has caused much confusion and difficulties during the implementation of program budgeting in several countries.

In Zambia, there were 3000 ‘activities’ under the Ministry of Health’s budget (FY 2011), with at least 5 subheads under each activity. This constituted around 15000 line-items! In Cambodia, there are 10,000 activities under the newly introduced program classification. This level of detail and complexity in the budget classification system is problematic on several counts, but the most fundamental issue is that it undermines the justification for moving to program budgeting.

One of the key justifications for moving to program or output based budgeting is that traditional budgets are too focused on details and inputs. Budget documentation is often voluminous with (sometimes) thousands of pages of tables detailing inputs for each of the budget entities. Performance based budget systems, on the other hand are designed to shift the focus from ‘inputs’ to ‘outputs’ or ‘programs’ - the services to be delivered by Ministries, the targeted results for these services, and the reporting on the these results. In this framework, accountability for the use of government resources (taxpayer’s funds) is separated so that:

- the government becomes accountable for allocating appropriate levels of funding to the ministries to meet the results; and

- the line Ministries become accountable for the achievement of these results, and the effective management of the inputs entrusted to them by the government (through the budget).

This shift in accountability has been difficult in practice. The Ministry of Finance in various countries has been reluctant to give up their absolute control over detailed levels of inputs (often disguised as ‘activities’). The Line Ministries were tentative too, as often for the first time, they were being held accountable for service delivery performance.

Too often, the response to these fears has been to continue providing detailed input and activity data in budget documentation and centralized expenditure control processes. The level of detail has often been so overwhelming that it diluted and to some extent undermined the focus on key service results, the very reason for the shift to performance budgeting systems.

Many other drawbacks have been experienced with respect to using activity level detail in the budget process:

- It made the budget management process excessively cumbersome. During the budget formulation process, too much time and effort is spent on detailing every cost driver of an activity, at the expense of determining its effectiveness or whether the activity can contribute to service delivery or program outputs.

- It made the budget execution inefficient. In Zambia, for example, it takes several weeks, every quarter, for the MOF to release funds for thousands of activities.

- Most of the information on ‘activities’ was either duplicative or unnecessary.

- If activities are expenditure categories (e.g. repair of buildings, training, capital expenditures on buildings, works, equipment, etc.), these can be captured through economic classification;

- If activities are internal work processes or the cost centers of the ministry (e.g. HR, Procurement, Budget, IT, Accounting, Internal Audit), as is often the case, these are unnecessary within the context of program budgeting. This level of detail is better suited for information within the ministry using spreadsheets.

But how to reflect capital and recurrent expenditures under programs?

One of the arguments supporting the use of ‘activity’ under program classification is that it reflects capital projects under programs. This objective is desirable. However, it can be achieved without using ‘activity’ - through mapping of spending units and projects to programs and sub-programs. Every ministry has spending units, financed either through recurrent or capital budget allocations (or a mixture of both). The thousands of schemes and sub-schemes, in which politicians are typically interested, can be treated as spending units. Since a program or sub-program should include information on recurrent and capital expenditures, all spending units, including schemes, should be mapped to the program classification in order to aggregate recurrent and capital expenditures.

What about spending units that contribute to more than one program?

Sometimes, it is argued that activities help in allocating costs to respective programs when a spending unit contributes to multiple programs. A spending unit at the top of the hierarchy (Minister’s office) or at the periphery (e.g District office) would present this scenario. An agriculture officer in a remote district will be contributing to multiple agriculture programs, including agriculture productivity and market access. This is one of the difficult scenarios under program budgeting. Such a scenario could be dealt in one of the two possible ways:

- If an overwhelming part of the budget of this spending unit – for example, 80% of the budget - is being allocated from one program, this spending unit should be mapped only to that program.

- If spending unit gets allocation from multiple programs in a mixed ratio – for example 30%, 20%, and 50% from three programs– there are two options to deal with this scenario:

- For the purpose of budgeting and expenditure recording, create 3 separate codes for a spending units, and map each code in a one-on-one relationship with the respective program. The Maldives government has opted for this option under its budget reform. Or

- Map such a spending units to general purpose ‘administration and management’ program

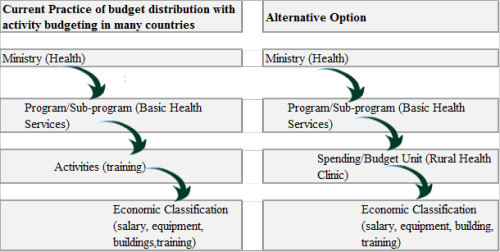

The underlying theme of the above options is that every spending unit code should be mapped to one program or sub-program. Using above design options under a programmatic budget approach is significantly simpler than using activity. Under this approach, the Ministry of Finance can approve the budget at program and/or sub-program level, while further distribution of budget to the spending units could be left to the ministry and program managers as shown below (See Figure 1). Budget execution controls and expenditure recording should be done at the spending unit level, and associated economic classification.

Figure 1: Simplified approach to program classification

In sum, the introduction of activities in the budget classification system has created enormous difficulties in many countries. Many governments are grappling with these issues even after 15 years of experience with program budgeting. Eliminating ‘activities’ in the budget management system of these countries can simplify the process. Not only will the information duplicity be avoided, but the reforms will be refocused to the basic objectives of the program budgeting – achieving budget performance results.

[i] Michael Schaffer, Senior Public Sector Specialist, Governance Global Practice, World Bank and Khuram Farooq, Senior Financial Management Specialist, Governance Global Practice, World Bank.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.